*

Last night, I was stewarding at an Eric Clapton concert, which mostly involves watching an Eric Clapton concert and getting paid for it (A+ job tbh). Because I’m ungrateful, I got to hoping Clapton would announce a special guest was sitting in with him on the next song, and out would come B.B. King. Much like every other time I’ve hoped this at a gig, of course, it was not to be.

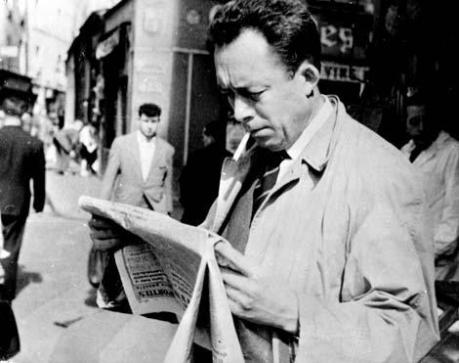

I used to be quite bad for performative social media grief when a celebrity died, so have tried to pipe down a bit this morning, but I’ve long known B.B. King’s passing would hit hard. And hit hard it did.

Still, King lived to the age of 89 and had an incredible life. There are people far better placed than me to write tributes and obituaries to the man, his life, and, of course, his music, so I’m just going to share a few nice songs, a little anecdote about how B.B. King legit changed my life and then I’m going to go and listen to the 50-song anthology I just found on Spotify while seeking said better writers out.

So in 2005 or 2006, Mum was working at the Montreux Jazz Festival and she brought a friend and I along with her to wander about the festival and soak it all in. Of course, this meant our lift back wasn’t until three in the morning, as far as I remember. So we wandered, we soaked, Montreux is a pretty incredible place even if you’re not going for a concert*, but there are limits. The last couple of hours of the night, we spent slumped on one of the sofas, flicking through the old concert clips they have there. That was where we discovered B.B. King. Reckon it was this clip.

I’m not gonna lie, dear reader, it was mostly the faces that caught our attention at first. Those faces. There aren’t many guitar players who are easily as fun to watch as they are to listen to, but B.B. King was one of them. But then the voice and the actual playing got to me – I think I must have made Daniel watch that video three or four times that night.

I had just bought my first guitar, mostly inspired off the back of discovering Muse, but the guitar was well on its way to becoming another expensive abandoned hobby when I heard The Thrill is Gone for the first time. Ten years on I’m still not really even fit to try and imitate B.B. King, but pretending I could got me properly interested in guitar, and also set me off on the path to… well, to becoming a tedious blues-rock bore for most of my teens, but there you go. Can genuinely see my life having taken a mildly different turn had I not come across that clip all those years ago, and it was all because of old Riley.

So that’s my anecdote. I’ll leave you with this lovely duet between B.B. King and Buddy Guy – stick around for the little chat at the end.

*livid that this doesn’t have video anymore

**the other activity for the day is working out whether I should have spent £100-200 to see B.B. King there on the couple of occasions he played while I was living in the area