Not saying I get self-conscious about how many war books I read, but having a weekly (more or less) record of my reading on here does sort of make it obvious. So been trying to diversify a bit.

I like this song for lots of reasons. It doesn’t seem to have any concept of pace or dynamics or go anywhere, which should make it a boring five minutes, but it’s not. Also, even though I know who Bobby Womack is and can just about recognise his voice, there are several points on the record where he sounds more like Marvin Gaye or Stevie Wonder, which is cool. Finally, the lyrics are kind of ridiculous! Enjoy that.

Last Man in Tower – Aravind Adiga

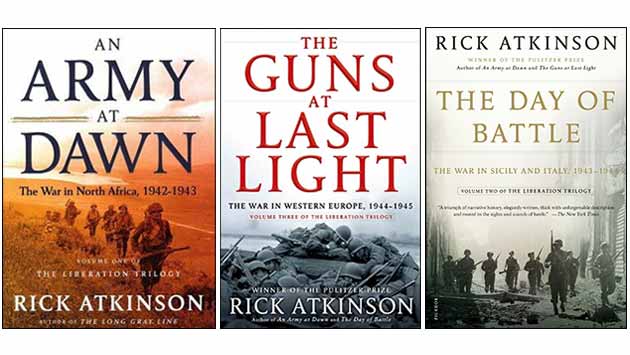

Book choosing strategies by me, your humble book reviewer:

Step One: realise you’ve got books overdue despite living half an hours’ walk from the library and being mostly unemployed

Step Two: renew said books three times until you feel guilty/it’s sunny out and you need an Errand to validate your day

Step Three: Go to the library, go straight to the 20th Century History section, do not pass go

Step Four: Are there any paperbacks on WW2 battles you haven’t read and that don’t look terrible? Grab.

Step Five: Feel guilty that you only read tank books by old white men. Drift through the novels section and pick up any famous and/or colourful-looking novels, preferentially ones that tick some demographic boxes!

Step Six: Double-check the tanks section.

Aravind Adiga’s Last Man In Tower is a novel, has a colourful cover and is written by an Indian fella – result.

It’s also very good! It’s very pacey and entertaining, while giving you a compelling look at redevelopment in Mumbai and how those involved respond to the changing city. There’s enough pretty prose about flowers to make you feel like you’re reading some art, without being too tossy. It’s often quite funny.

It’s a story that feels very universal (to a certain extent it’s a gentrification tale like what we can’t stop talking about in London) and yet, through the protagonists’ religions and the particular practices of Indian construction moguls and residential societies, feels very specifically “Indian”. I don’t know if it is! Maybe it’s actually a weird pastiche of Mumbai life with terrible politics and I only enjoyed it because I know nothing about India. But it did that nice thing of making me feel like I understood completely different lives to mine a little bit better than I do now.

Good, imo.

Ghost Fleet – Peter Singer and August Cole

It’s not as good as Red Storm Rising, but it tries its best. Could leave it at that, really. Peter Singer and August Cole’s Ghost Fleet portrays a well-researched version of how World War Three could play out, drawing on trends in military technology that are so integral to the book they have footnotes. The tech seems plausible to me, an almost-layman. I mean I cited Singer (it’s not the philosopher one) in at least one university, so I’m not about to doubt that side of things. There’s a lot of near-future war – killer robots, cyber-warfare, space warfare, etc. The near future setting allows this all to be described to contemporary readers – there are enough characters who were around in the early 21st Century and are suspicious of all these darn drones to justify explanations and comparisons. So you know, if it was just a more engaging way of examining how war might look tomorrow, that’d be OK.

But of course, it’s a thriller, and so it has to have all that goes with that. The hubristic enemy admiral who literally mutters/proclaims Sun Tzu quotes to himself throughout the book and the final battle. The officer with daddy issues. The gruff old sailor who knows the old ways are better. etc. etc. The literal femme fatale. The U.S veterans of Afghanistan who become guerrillas in their own home towns and isn’t this ironic. Nothing outright awful but there are a lot of pulpy clichés. The narrative itself, IDK how much I buy it. Red Storm Rising succeeded, as I recall, by making it clear that the whole thing was a desperate gamble by the Soviets that had to bring quick victory or complete defeat. So in that book, the “at first we lose but look through sheer American grit and force of will and good tanks we ultimately triumph” arc worked. I won’t spoil Ghost Fleet but TBH, I think that quote is a pretty generous characterisation of how it plays out.

Anonymous play a crucial role in this book, is all I’ll say.

IDK, it’s alright, I was reading it whenever I had a spare moment for a weekend, so it wasn’t terrible I guess but eh. Here’s an interview with the authors that might be as interesting in terms of technology and trends, really.

War Stories – eds. Sebastian Faulk and Jorg Hensen

Quite hard to review an anthology, it turns out! There’s good bits and OK bits, very few that I’d consider Bad. As a collection, it is very WW1-heavy, I don’t know why. Vietnam gets a big showing, and I think there aren’t any excerpts later than the Gulf War. There’s an interesting effort to avoid obvious choices. I’m not as well-read on war fiction as you might expect from this blog, so I can’t comment on all the choices, but, for example, the only Hemingway excerpt is from Farewell to Arms, and it’s not even one of the more military ones in there (I’d have expected the chaotic retreat scenes to feature over this one) – but it did have the side-effect of reminded me of the horrific ending to that book (rude). Similarly, Vonnegut only appears as the foreword to Slaughterhouse Five. It makes it much more likely that you won’t have read any of it, which is nice. There’s a fairly decent spread of perspectives and sides of the wars, including several translations, which is nice.

Probably more of a “dip in and out” than a “read for three hours straight while you’re waiting to meet someone for a fun evening out” book, as it turns out the Holocaust is not good pre-drinks material. Who knew.

Leningrad – Anna Reid

OK so this was a war book but it was written by a woman at least, so there’s some sort of change at least.

I don’t know as much about the Eastern Front as I should! My previous attempt to rectify that was …not successful. Part of the issue, I think, is that while histories of the Western Allies are far from apolitical, there is so much of an agenda when it comes to discussions of the invasion of the Soviet Union. You feel constantly on the look-out for distortions, knowing that there have been several revisionist understandings of the war already. Reid points out and rebuts, for example, the Cold War efforts to excuse the Wehrmacht as an institution from the crimes it committed during the war.

Fortunately (and unfortunately), this isn’t a military history. I still don’t know much about Kursk or how the Red Army recovered from catastrophe to win the war or enough cool facts about the T-34. What I do know is that the siege of Leningrad was bloody horrific.

Attention tends to be paid to Stalingrad, for probably obvious reasons, but on the numbers alone, this is a different scale of horror. Reid estimates that between 1/3 and1/4 of the city’s pre-war population perished during the siege, or about 700,000 people. Most of these were from starvation.

Food, its absence, and how people tried to get hold of it, are at the heart of this book. Compellingly told through the use of diaries, memoirs, and interviews with survivors, Reid is able to give devastatingly personal stories of how the siege reduced people to shadows of their former selves. Poor planning, corruption, and a blockade set up with the deliberate intention of starving the civilian population created a nightmare situation over the almost 900 days of the siege.

It’s heavy reading, made somehow more bearable by all those diaries and memoirs. It’s a very human book, despite the horrors it recounts. You will obviously feel a little bit hesitant to ever describe yourself as “hungry” again.

The military side of things, as I say, is less effective. It might be because Leningrad wasn’t a decisive front, but there’s not an enormous amount of “this regiment attacked on this day with these tanks” stuff, which probably sounds like a positive to you fools. It makes it slightly harder to follow the overall situation of the war outside the city, however, and where Reid does focus on military bits, it’s a bit rushed and confused. That said, there’s one Wehrmacht perspective in the book, the diary/memoir of a German captain occupying outlying villages, and it’s pretty compelling.

Still. Good, depressing, more tanks required imo.